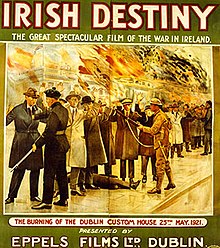

'IRISH DESTINY' Courtesy of the Irish Film Institute

With renovation work

beginning at The Motion Picture Conservation Centre at Wright-Patterson US Air

Force base in 1991, a nitrate copy of a film, believed lost, was discovered on

a shelf in the facility. Operated by the US Library of Congress near Dayton,

Ohio, the centre consisted of two divisions, the Film Vaults and the Motion

Picture Preservation Laboratory. The Film Vaults facility provided a safe

storage for the highly flammable nitrate film, which was the main method of

making motion pictures from its beginnings in the early twentieth century, by

maintaining the environment at a regulated temperature of 52 to 55 degrees Fahrenheit

and a relative humidity of between 35 and 40 percent. What had been discovered

was a copy of the first ever domestically produced feature film in the then new

Irish Free State in 1926. An Irish American, Patrick Sheehan, who worked in the

Library of Congress in Washington DC, made a remarkable discovery, a copy of

the film, lodged there for copyright purposes and had lain untouched and

unnoticed for decades. The 35mm film was in a perilously fragile state and the

US authorities initiated preservation at a specialist laboratory in California.

For many movie goers, the

1993 movie ‘Cool Runnings’ starring the late John Candy and Leon Robinson

introduced the unusual premis of a bobsleigh team from a nation that rarely

saw snow and ice, competing in the 1988 Winter Olympics. In St Moritz,

Switzerland, in January 1927, an Irish bobsleigh team was beating seasoned

winter Olympic nations in bobsleigh races and setting track records in the

process. The team was led by Paddy Dunne Cullinan who was an accomplished

sportsman and well known in horse racing circles as the owner of the Carrollstown

Stud near Trim in County Meath. He had taken over the running of the stables

from his father in 1923. St. Moritz had been developed by British entrepreneurs

after the First World War and its famous Cresta Run attracted thousands to

watch the incredible speeds achieved by the ‘boblets’ as they flew down the

hill. In the early twenties it became popular with horse racing jockeys from

both Britain and Ireland. Cullinan began visiting the resort from the early

twenties and would at one stage he would hold the world record for the fastest

decent on the Cresta track.

On Saturday August 25th

1925 at the Arcadia Ballroom near the Bray seafront, the Irish Cinema and

Theatrical Garden Party was held. It advertised that ‘stage and screen stars

will be in attendance. Outdoor cabaret

shows have been arranged’ and that there would be ‘non-stop dancing’ from 8pm

to midnight with the music provided by the Harrison’s and Adelaide Melody

bands. In newspaper advertising at the time one of the main attractions of the

Garden party was a ‘Ladies Face Competition’ with the prize announced as an

‘engagement in the new Irish film, ‘Irish Destiny’ for the winners’. It was a

gamble for the novice film producer but the publicity of both the competition

and the subsequent reporting, including photographs of the winner elevated the

film from an amateur production to an attempt to create a fledgling Irish film

industry on the back of the expected success of the Irish Free State’s first

venture into domestic movie production.

The Bray competition was

won by sixteen-year-old Evelyn Henchie, the daughter of a Commercial traveller

who lived on Palmerstown Road in Rathmines. The competition runner ups, Eileen

Grennan from Bray and Miss Hogan from Dublin were offered smaller parts in the

forthcoming production. ‘Irish Destiny’ was the brainchild of a Dublin Pharmacist

and leading member of the Dublin Jewish community Dr. Issac Eppel. Eppel had

begun to act as an amateur impresario by booking acts for the Rathmines Town

Hall variety shows. He used the funds generated from that enterprise to

purchase the Palace Cinema on Pearse Street.[1]

The cinema was often used as a meeting centre for the Irish volunteers in the

run up to the 1916 Easter Rising and as a meeting place for dissident and

underground groups.

Eppel decided to not just show movies at his cinema but to make the first feature film to be entirely made in the new Irish Free State. In September 1925, Eppel’s Films Limited was registered in Dublin by Eppel with a capital of £5,000.[2] Eppel acting as both producer and script writer, gathered a crew and employed both professional and amateur silent actors to perform in his movie. He employed a veteran of the British silent screen, Preston born George Dewhurst to direct the film. However, whether there was a disagreement between Eppel and Dewhurst or that Dewhurst did not want his name associated with the picture, the opening credits state that the film was ‘written and directed by I. Eppel’

The script was written by

Eppel and shown on screen through 120 text frames. Some of the other crew

included Joe Rosenthal who was in charge of cinematography and Jack Plant who

created the special effects. In September 1925, filming began with outdoor

scenes filmed in Enniskerry, County Wicklow, which became the fictional town of

Clonmore. When O’Hara arrives back in Clonmore by train, the railway station at

Rathdrum doubles as Clonmore. Scenes are filmed around Glendalough and at the

Powerscourt waterfall. The chase scenes were filmed near the Sugar Loaf

mountain while the set piece of the film, the battle scene was filmed on the

open spaces of the Wicklow hills. The cast and crew then travelled to film

studios in London to film the interior scenes. Eppel then edited the movie in

London against the deadline of having it ready to screen on the tenth

anniversary of the Easter Rising.

According to the Movie

website IMDB, the film’s plot was,

‘When

the notorious "Black and Tans" arrive at his village of Clonmore, IRA

man Denis O'Hara discovers a plan to raid a secret IRA meeting, and he races to

Dublin to warn his colleagues. He reaches the city but is shot and captured by

British soldiers. Denis is imprisoned in Kildare but manages to escape along

with his fellow prisoners. Believing him to be dead, his mother goes blind from

the shock, and his girlfriend Moira is abducted by fellow villager Beecher, who

is in league with the Tans. Denis arrives back in Clonmore just in time to

rescue Moira. With the burning of the Customs House in Dublin, the War of Independence

is soon over and a truce is reached with the British.’

To give the film a sense

of authenticity, Eppel added newsreel footage filmed in Dublin during the War

of Independence including the destruction of the Custom House in Dublin and the

burning of Cork. This was cut with recreations filmed around the city making it

at times difficult for the viewer to differentiate between fact and fiction.

When Eppel was finished editing and his silent movie was ready, it consisted of

eight reels and was seventy-three minutes long. According to the Trinity

College database,

‘There

are graphic depictions of "occupying" British soldiers being attacked

and shot dead, a spectacular mass jailbreak by republican internees and scenes

of jubilant villagers celebrating the success of the "armed

struggle". The film also features a parish priest openly condoning the

violence and assuring grief-stricken parents that their son's valour is

"God's will" and will bring "peace and happiness to Ireland".

A racy sub-plot involves O'Hara's sweetheart, primary school teacher Moira

Barry, being abducted and threatened with rape by a sinister gang of poteen

distillers led by an "informer" and his malevolent dwarf sidekick.’

A more detailed

description of the film taken from Irish Destiny shows that it was set during

the War of Independence and up to the Anglo-Irish Truce of 1920- 21. At the

heart of the film is the love affair of Denis O'Hara and his fiancée, schoolteacher

Moira Barry. The film scenes are interwoven with incidents from the war shown

through newsreel material including the burning of Cork City[3] and of the Customs House[4], and the mass escape from

the Curragh Camp[5].

In the peaceful village of Clonmore, Black and Tans arrive to terrorise the

people. O’Hara’s mother is badly affected by these disturbances. Her eyesight

begins to fail from the shock and in reaction to the unfolding events in the

country, her son decides to join the IRA and is handed a weapon. Following an

ambush of a troop convoy by the IRA, an important communique is found on one of

the officers. This is the major battle scene and with a sense of reality it

portrayed casualties on both sides. The battle is depicted as a David v Goliath

attack. The intertitle[6] states,

‘at dawn, a small number of volunteers with only a few rifles and shotguns, prepare to attack lorries of powerfully equipped and numerically superior forces of military and Black & Tans.’

The films showed the IRA

is numbered at thirteen and they take on three tenders of British forces with

approximately fifteen men on each, a total of forty five men. As the battle

progresses, the British casualty numbers increase and eventually the survivors

climb onto one tender abandoning the other two. This indicates thirty

casualties on the British side. In this attack and a subsequent raid on an

abandoned house the IRA Volunteers were using there were two IRA casualties. To

lend sympathy to the Irish cause in the film, the Black and Tans abandoned the

dying and wounded as they fled, while the IRA are seen picking up both of their

casualties and removing them from the battlefield.

O’Hara is asked by

Captain Kelly, the commandant of the Clonmore Battalion, IRA to take the

information to the IRA's Dublin headquarters. He gets a horse from the jarvey’s

stable but before setting off he sees Moira and tells her why he needs to go to

Dublin. After he leaves, Moira's horse is startled by a shot, and O’Hara

gallops to catch the trap. Also on the scene is Beecher, leader of a gang of

poteen-makers based at the Haunted Mill. Beecher offers to look after Moira,

but when she recovers, he tries to molest her. He becomes suspicious of Denis'

activities. Arriving at the 'Meeting of the Waters', Denis rests his horse, but

he is spotted by a British army sentry on the bridge who opens fire and this

alerts a British army motorcyclist. During the chase, Denis shoots the soldier

on the roadway and steals his motorbike, which he uses to get to Dublin. The

film footage includes a camera mounted on a van filming the following

motorcycle through the Dublin streets. As he is driving down O'Connell St,

Denis believes he is being followed. At the IRA headquarters, Vaughan's Hotel, Parnell

Square, Denis delivers the message to an intelligence officer.

However, the Black and

Tans arrive outside on the Square, having been tipped off by Beecher, and Denis

is shot and captured. His parents and others, including Captain Kelly, believe

he is dead, but he is being cared for in a hospital. A sympathetic nurse

smuggles out a message[7], and when he recovers, he

is imprisoned at the Curragh Detention Camp. There, in September 1921, Denis,

along with 200 other prisoners, escape from custody. Despite a search,

including by aircraft shown through a newsreel footage the aircraft flying in

formation, Denis remains free. He is given help by an old woman, and eventually

finds his way to Shanahan’s, where he finds Kitty, the jarvey's daughter. He

enquires about Moira, who has gone by car with Beecher who falsely tells her

that there is a wounded IRA Volunteer on the road needing attention. When he reaches

the Mill, Beecher stops the car and violently drags the protesting Moira into

the Mill. Meanwhile, Denis and Kitty get on a horse and give chase. In the

Mill, Moira is tied to a pillar and is drunkenly assaulted by Beecher and the

dwarf poteen-maker, as Beecher accuses her of providing information about the

Tans to the IRA. A dispute breaks out between Beecher and the dwarf which leads

to Beecher shooting the dwarf dead. As a result of the shooting the Mill is accidentally

set alight. Denis and Kitty arrive at the Mill and Denis becomes locked in

struggle with Beecher, whom he subdues. He frees Moira as the flames engulf the

Mill and Denis and Moira join Kitty in safety outside, as the Mill burns. Peace

descends on Clonmore with the Anglo-Irish Truce. People dance on the roadway,

while in Dublin crowds celebrate the coming of peace. Though blind by now as a

result of the nervousness induced by the trauma of her son’s actions, Mrs

O'Hara is happy to have her son home, where he arrives with Moira, as his

father and the local priest give their support

There was little surprise

that the film was banned by the British censorship board but Eppel believed

that much needed revenue to recoup his investment would be generated by the

Irish audiences’ response being publicised in the United States. The novelty of

the first Irish film was expected to play well with the Irish diaspora across

the United States. On March 24th 1926 the film was premiered to cinema owners

and managers at the Metropole Cinema on Dublin’s O’Connell Street, nest door to

the iconic GPO. Also in attendance was much of the cast including the extras,

many of whom were IRA men who had seen action during previous decade. Once

seen, the cinema managers or owners would then bid on which cinema would get

the public premiere and the all-important first run. After the screening the

owners of the Corinthian Cinema on Aston Quay signed what was described as ‘the

highest price paid for a film in Ireland’. On April 3rd 1926, the film opened

in the Corinthian.

This was the opening credits of the film, listing the characters and the actors.

The new Irish State was

emerging from a war of independence with Britain and struggled through a

violent and vicious civil war and any movie that would have been seen as

perhaps re-opening some of those wounds was always going to be controversial.

There was a genuine fear of the threats of violence against those involved with

the film. As a result, many of those who appeared in the film did so by using pseudonyms

but appeared with the real names in Irish newspaper advertisements. The actual

cast were,

Paddy Dunne Cullinan as

Denis O'Hara. This was Cullinan’s only film credit. He was employed for the

role primarily for his horsemanship. He had been a popular sportsman in Ireland

especially in the equine business. He was a well-known point to point trainer

and jockey and a number of his horses would go onto win some of the racing

world’s biggest races including the Irish Grand National. He was a leading polo

player in Dublin’s Phoenix Park and while on holidays in Europe discovered

winter sports including skiing and bobsledding.

Frances McNamara as Moira

Barry, a schoolteacher and Denis' fiancée. This was Ms. McNamara’s only screen

credit.

Daisy Campbell as Mrs.

O'Hara, Denis' mother. Ms. Campbell was an English actress, popular on the

London Theatre scene, who had been in a number of silent pictures prior to her

role in Irish Destiny. She was well known for portraying aristocratic white-haired

matrons and Lady’s. Her final film role would be as Mrs McPhillips in the film

‘The Informer’ based on Liam O’Flaherty’s work about an IRA informer. But she

was not the first choice to play the role.

Originally cast as Mrs.

O’Hara was Sarah Allgood, who had been the first Irish voice to be heard on

radio in the British Isles appearing on the forerunner of BBC Radio, 2LO. On

the day before Eppel showed his film to the assembled cinema owners in Dublin, he

appeared in the Dublin District Court before Justice Piggott. He was being sued

by Allgood under her married name Sarah Benson for a breach of contract as

Eppel had agreed to employ her for two periods of six days each, six in Ireland

and six in the London studios at a rate of four guineas per day. But when she

arrived in Greystones in September to begin filming, Eppel told her that she

looked too young to play the part of the mother. She told Eppel that she had

played motherly roles in the past and said ‘if you give me the part, I will

give you the emotions you want’ but Eppel said no and Allgood retuned to

London. She won her case and was awarded £29 8s.

But Allgood wasn’t the

only one to take Eppel to court. A year after her case was heard, another case

was taken against Eppel. John Byrne, a horse and jarvey owner of Queensboro

Road, Bray took a case against Eppel for the non-payment of £30 for the hire of

his horse and cart. He claimed that he had to be on call for a full month but

would only be used when weather was permitting and this was only fourteen days.

He sought payment for the other days. He said in court that his pony and trap

was used in the ‘runaway scene’ and that he would have to travel to the Sugar

Loaf, Greystones or Shankill depending on the filming schedule. He was awarded

£14 by Justice Davitt at the Dublin Circuit Court.

Clifford Pembroke as Mr.

O'Hara, Denis' father. He was born Thomas Jones Williams in Pembrokeshire,

Wales in 1867 and appeared in over a dozen British silent films. He died in

London aged sixty-five, his last film was The Woman from China in 1930, written

by George Dewhurst who directed Irish Destiny.

Brian Magowan as Gilbert

Beecher, a gang leader of the poteen-makers. McGowan appeared in a number of

the early Irish located silent films with Fred O’Donovan including Knocknagow

and Willie Reilly and his Colleen Bawn.

Cathal McGarvey as

Shanahan, a jarvey. McGarvey was a well-known and popular veteran Dublin

entertainer known for his performances on stage at the Queens Theatre. In 1924,

he had been the beneficiary of a celebration night at the Queens and appearing

with him on stage was the aforementioned Sarah Allgood and the newspapers reported

that a highlight of the show was his music and comedy duets with Jimmy O’Dea.

He also recorded for the Gaelic League with future Irish president Douglas

Hyde. His fame from the film would be short lived as he passed away in November

1927.

Evelyn Henchie as Kitty,

Shanahan's daughter. Evelyn, having won the competition in Bray, was 16 years

old when the film was made, only appears in outdoor scenes, because these were

filmed in Ireland. She was not allowed to travel to London where the interiors

were shot in a studio.[8]

Later Evelyn would marry Sir Raymond Grace and become known as Lady Evelyn Grace,

living in Dublin splendour on Sussex Road, off Leeson Street in Dublin. She

would become well known as a dog breeder and exhibitor of pedigree bull

terriers.

In 1927, when the movie

opened in New York, the Evening Independent reported on April 20th that,

‘Peggy

O’Rorke, the young Irish woman who plays the leading part in ‘Irish Destiny’,

the all-Irish film play will arrive in New York in June and it is considered

likely she will appear in pictures in this country. She will also make personal

appearances with the film, as it is shown in theatres throughout the country. ‘

While Eppel was in the United

States promoting his movie, his Palace Cinema on Pearse Street[9] was badly damaged by fire.

In a telegram from New York, he immediately informed his sister Olga Weiner,

who had been running the cinema in his absence, that he intended to rebuild and

refurbish the cinema and reopen it under its original name ‘The Ancient Concert

Rooms’.

A letter appeared in The

Irish Times on October 1st 1984 from Evelyn reminisced about the making of

Irish Destiny and wondered, "Does anyone else remember?" The letter

stirred some memories, but all copies of the film were believed to be lost. And

that was almost the end of the matter until, a few years later, by truly

serendipitous coincidence, two original colour posters advertising the film

were found under linoleum during a house renovation in Ringsend, Dublin.

The Irish Film Archive triggered a painstaking worldwide search of film archives on the remote chance that a copy might have survived somewhere. Then Patrick Sheehan, who worked in the Library of Congress, made his remarkable discovery, a copy of the film, lodged there for copyright purposes.

Kit O'Malley as Captain Kelly, commandant, Clonmore Battalion, IRA. O’Malley acted also as a consultant on the movie as well as acting in it. 'Kit' O'Malley had been Adjutant in the Dublin Brigade of the IRA during the War of Independence and he also assisted in directing the battle scenes in the film.

Val Vousden as the Catholic

Priest. Carlow born Bill McNevin had a long career on stage, radio and in

films. In 1914 while travelling in a repertory company in England he joined the

British army during World War One and saw action of the green fields of France.[10]

Tom Flood as Intelligence Officer, IRA headquarters. He was involved on the attack on the Custom House. Tom Flood was arrested at the Custom House while is brother Eddie who was also on the raid, escaped. It is said Tom was jailed in Mountjoy and sentenced to death. Only to be reprieved first by appendicitis and then the Truce.

(The unusual story of Tom

Flood can be found here https://www.customhousecommemoration.com/2018/04/21/mystery-tom-flood-harry-houdini-custom-house-custom-house-burning/

)

The film, despite its pre

publicity did not wow the critics. The Irish Independent reported on that day

after it had been shown to Cinema owners and newspaper reporters that,

‘What is known an s a trade

show; of the film ‘Irish Destiny’ was given ay the Metropole today. The house

was crowded and included many of the men who formed the backbone of the old

pre-truce Volunteer force who carried on the great struggle against Great

Britain. Frankly, we were not impressed by the production. It has, however, several

good points but it has bad ones as well. Opinion will very likely differ on

those matters.

To begin with, if we exclude

what we might describe as the Hollywood atmosphere which surrounds part of it,

the film is an advance from the point of view of film production on anything

attempted here so far. The photography leaves nothing to be desired, the light

is good, the scenery quite pleasing and with the exception of the work of one

of the artistes, the hero, torn between love and duty, is a tribute to Irish

talent and is creditable to those who took part.

They are worthy of a better

story, a more suitable groundwork, something which would bring out more and, in

a manner, which would appeal to those who lived through the trying period, the

real spirit of those times, with particular relation to the work of the

Volunteers. There is nothing derogatory said of them, but there is little

either that is forceful or satisfying. What outsiders will think about it will

probably be quite different. We see a disconnected story. People in America may

consider it all right but as an insight into the past it is a pity that

something better could not be put upon the record.

There are clashes in arms which

are vivid enough and incidents which are week. The Customs House burning is

amongst the latter. It would probably be difficult to reconstruct scenes to

depict those happenings and to have them brought out with more thoroughness, is

probably expecting too much. We are given the impression of what the agony of

the struggle meant in the homes of the people, to the mothers whose sons were

fighting and to the men themselves as well. This is all right and is well acted

by Daisy Campbell as the mother, Clifford Pembroke as the father and Val

Vousden as the parish priest. Cathal McGarvey as the jarvey is suited to the

part and Peggy O’Rourke and Una Shields, the latter as the heroine cover

themselves well. ‘Kit O’Malley’, the IRA Commandant and Denis O’Shea, the hero,

are also good. Bryan McGowan as the poteen maker and treacherous character,

handles his role skilfully but the scene in his den appears to strike a foreign

note so as this country is concerned.

We are hurried through the

hectic period from 1916 to 1921 in whirlwind fashion. We see Black and Tans,

military tanks, armoured cars and we get glimpses of war. Sections of the

audience applauded. British arms were answered with hisses and we came away

unconvinced by the story or the theme.’

It must be remembered that for many cinema goers

accustomed to US and British made movies, the views of an Irish countryside

were a novelty. For those viewing the film in rural Ireland, who had often read

or heard about the importance of Vaughan’s Hotel to the Michael Collins led

war, would have been exited to see action filmed outside the Parnell Square

location. The use of actual newsreel film confused the supposed timeline of the

film. There was some confusion in the film about its exact periodisation in

1921. While the escape from the Curragh Camp occurred on 9 September 1921, it

appears in the film’s timeline to be followed by the Anglo-Irish Truce, which

came into effect on 11 July 1921, two months earlier. The impression one is

left with it is that it is the Anglo-Irish Treaty of December 1921 which ends

the film.

The other point made by

the Irish Independent was scene filmed in the poteen makers disused mill

headquarters. He had kidnapped the heroine, O’Hara’s girlfriend and his actions

intimate that she is about to be raped. The fact that a number of criminals are

there would seem to suggest that she was going to be gang raped and when one of

the criminals developed a conscience, he was killed by the villain. She is tied

up in a scene reminiscent of a BDSM scene from the modern era. The scene itself

seems gratuitous and unnecessary to the plotline, as the kidnapping alone would

send the hero into action to save his girl. There was also criticism from the

Catholic Church of these scenes especially as a Parish priest played a central role

in the film, although his acceptance of IRA violence was subsequently called

into question when it was first shown in cut form in Britain.

On the front cover of Peter

Cotterill’s book ‘The War for Ireland 1913 -1923’ is a photograph that is

credited as,

‘This remarkable

photograph, taken on 14 October 1920 by 15-year-old John J. Hogan, an

apprentice photographer, is of British intelligence officer, Lt Gilbert Arthur

Price RTR, only seconds before he was killed in a gun battle with the IRA

during a raid on the Republican Outfitters in Talbot Street, Dublin. IRA leader

Seán Treacy was also killed during this incident.’

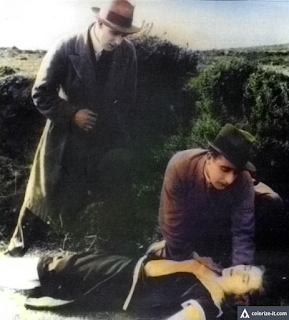

The same photograph captioned ‘14 October 1920 Lieutenant Price, British intelligence officer, opens fire on Sean Treacy in Talbot Street, Dublin’ appears accompanied by an article on the January 1919 Soloheadbeg ambush in the Spring 1997 issue of History Ireland.[11] The photograph while it was taken by Hogan, who would later become the Chief Photographer at the Irish Independent, it was not from events in 1920 but a photograph of Paddy Dunne Cullinan acting out the seen where he fires on the ‘Black and Tans’ who attempt to arrest him outside Vaughan’s Hotel.

The critic noted that the

film "was presented at Daly's Theatre[12]

last evening to an audience composed largely of persons of Irish birth or

extraction" and described the acting and direction as "very

amateurish" and the photography as "deficient". But the audience

didn't give a hoot. "The scenes of Irish Destiny elicited constant waves

of applause. The spectators manifested their enthusiasm when the Black and Tans

fell, and they hissed, as in the days of old melodrama, when a Black and Tan

bullet struck an Irish Volunteer". The film was shown at Daly’s for five

weeks. When it was released in Britain under the title ‘An Irish Mother’ the

Daily Sketch said of the film,

‘There

is freshness as well as the charm of naivete about this Irish contribution to

the screen, albeit it would be useless to deny that the firstling has faults

which would or should not be found in the output of more experienced producers.’

It was re-released in

Ireland in 1927 with extra scenes of newsreel footage added and it continued to

sell out cinemas but despite its popularity in Irish, audiences in Ireland

alone would not return Eppel’s investment on the movie. The English premiere of

the edited version of Irish Destiny, retitled An Irish Mother, took place on

October 27th 1927 in Newcastle. The Kinematograph Weekly reported,

‘An Irish Mother The premier presentation in England of Mr. Eppel's Irish-made picture, "An Irish Mother." took place on October 27 at the Futurist, Newcastle, where an excellent attendance was addressed by Walter C. Scott. chairman of the North Western branch of the C.E.A. who briefly welcomed this Irish production to the screen. Before the picture a prologue was presented, showing "Mother Machree " seated at her spinning wheel, whilst an unseen vocalist sang the song of the film.’

On December 1st 1927, it opened in two picture houses in Liverpool. The project drove Dr Eppel to the brink of financial ruin and he emigrated to England in 1928, having sold the Palace Cinema to his brother and brother-in-law and the rights to his film to a European production company[1]. His Eppel Film Company had debts of £13,000 when he met with creditors at his solicitor’s office[2]. His marriage was also troubled and he moved alone to England where he resumed practice as a GP, never making another film although the trade papers reported that he had been appointed in April 1929 as the Four Northern Counties representative of the British Talking Pictures Company. Before he left Ireland in 1928, Eppel found himself in Court once again in relation to his movie. He appeared before the Irish Supreme Court as a case reached the top court for a decision. He sued Ernest Tahon of Brussels for unpaid instalments of £500. The court awarded £375 to Eppel when the objection to a Tahon affidavit being taken by an English commissioner was rejected. Eppel died in Kingston-upon-Thames in 1942. By then, Irish Destiny was already long forgotten. That was until the copy used in New York theatres was found in the film archive.

On December 11th 1993 at

the National Concert Hall, Dublin, the complete restored copy from the Library

of Congress was screened at this invite only event accompanied by a new score

written for the film by Michael Ó Suilleabhain. 'Mother Machree' and 'Danny

Boy' were recommended as musical accompaniments on the film itself when it was

first released. The event was attended by President Mary Robinson. Alas the

woman who lit the spark to find a copy of the film Evelyn Grace (Henchie) died

the previous March.

The National Concert Hall

is once again the venue for a special screening in 2006, the eve of St

Patrick's Day. The score was again performed by Mícheál Ó Súilleabháin,

together with the RTÉ Concert Orchestra conducted by Prionnsías Ó Duinn. It was

described in the Evening Herald, ‘It is an intriguing aide-memoire for a

society reflecting on the 90th anniversary of the Easter Rising’.[15]

[[1] The Bioscope, June 20th 1928

[2] The Bioscope March 8th 19281]

Later to become the Academy Cinema and Theatre

[2]

September 10th 1925, The Bioscope

[3]

December 11th 1920

[4]

May 25th 1921

[5]

September 9th 1921

[6] An

intertitle is the subtitle screen in a silent movie

[7]

The message is never seen reaching its intended recipient, Moira.

[8]

IMDB

[9]

Originally known as Great Brunswick Street, the street was renamed after the

executed 1916 leader Patrick Pearse in 1925

[10]

From his autobiography ‘Val Vousden's Caravan.’

[11]

Page 43

[12]

New York

[13]

The Bioscope, June 20th 1928

[14]

The Bioscope March 8th 1928

[15]

Irish Times March 11th 2006